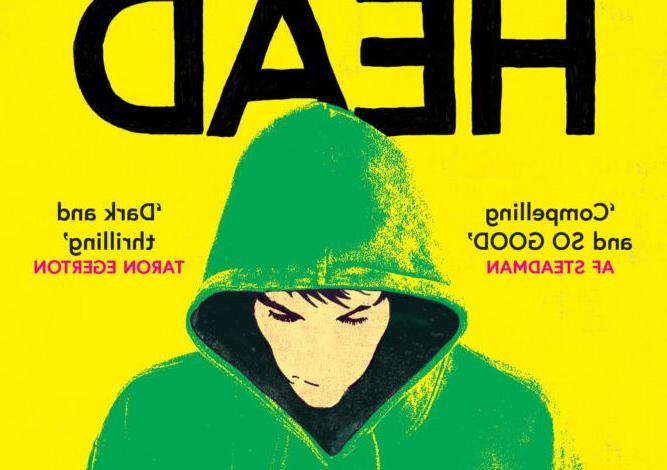

An experienced mental health therapist and author, Josh Silver asks some important questions with his debut novel HappyHead. First, he wonders, whether happiness is an illusion or a notion prescribed to us by others. Ultimately, he suggests that we individually define happiness and need to resist many of the systems in place that manipulate our feelings about happiness.

A dystopian thriller set in Scotland, HappyHead explores the potential for mental health to have a shady side if those designing therapy wish to use behavior modification to engineer a more nearly perfect society. While not an Aldous Huxley model, Silver does ponder the power that the desire for happiness has on us.

To develop his theme, Silver creates seventeen-year-old Sebastian Seaton who feels deeply. Although Seb comes across as quiet and intense, he is actually, smart, funny, and kind. Because his parents worry about their son’s unsettled persona as well as his insecurities, they sign Seb up for the HappyHead Project based on the research of Dr. Eileen Stone. This “cutting-edge program” not only offers participants the opportunity to find “enduring happiness” but promises to equip them with “the tools needed for future success.”

Upon arriving on the grounds, Seb considers everything about the institution to be unusual and antiseptic. He is stripped of his comforts: phone, David Bowie music, and Jolly Ranchers. While the program strikes him as a laboratory experiment with assessments, hospital green uniforms, chip insertion, and other manipulations, Seb is determined to make the experience a successful one so as to please his parents. The teens are grouped, and two of Seb’s “Acid Green” group mates stand out: Eleanor Banks is not only competitive but somewhat cold and judgmental to the point that Seb calls her the “spawn of Lucifer.” Another member, Finneas Blake is defiant and determined to discover the truth about this place. He tells Seb not to trust the camp authorities. The two eventually forge a bond.

In the opening ceremony, Madame Manning reports to the group: “You are all in danger. . . . We have seen a drastic rise in emotional dysregulation among young people. . . . Depersonalization and derealization are up. Interpersonal and communication difficulties are areas of significant concern. You are progressively vulnerable to invalidation. Self-invalidation. You feel stuck. Lost. Loneliness is an infection so strong in some of you that you no longer know how to function in our society” (31).

While some of this rings true with Seb, his radar tells him to tread with caution. After all, there is a perimeter fence, and the group is locked in, their lives monitored and regulated by guards in overalls. The Home’s motto is “commitment, growth, and gratitude lead to happiness.” As time goes on, just like in Animal Farm by George Orwell, the word obedience is added and the sinister begins to escalate as the groups are pitted against one another for the sake of survival in “the game,” similar to the playbook of another dystopian writer, Suzanne Collins of The Hunger Games series.

Eventually, the reader realizes that the youth in this experiment have been hand selected; each one has a predisposition to feel things at a different degree than is typical. Because personal experiences move the dial, HappyHead will tailor a treatment to suit each individual. As both Finn and Seb realize that Manning has a PhD in BS and that their freedom in this “glass asylum” is not guaranteed, their very lives may be in danger.

Besides the multiple allusions to David Bowie’s music and to additional artists who explore Big Brother or the human search for utopia, some of the other insightful aspects of Silver’s book include his metaphor for life and his analysis of the unhappiness epidemic in the world. Sadly, many people think they need to deny the self in order to find acceptance, happiness, and fulfillment. However, we would do better to realize that problems are part of life and can be used to better ourselves. Instead, many people view problems as stumbling blocks rather than as stepping stones, forgetting that we have the capability and the internal resources and resilience to make changes at any point so as to make vital progress.

- Donna